Three possibilities come to mind:

Is there an evolutionary purpose?

Does it arise as a consequence of our mental activities, a sort of side effect of our thinking?

Is it given a priori (something we have to think in order to think at all)?

EDIT: Thanks for all the responses! Just one thing I saw come up a few times I’d like to address: a lot of people are asking ‘Why assume this?’ The answer is: it’s purely rhetorical! That said, I’m happy with a well thought-out ‘I dispute the premiss’ answer.

Confabulation.

Look at split-brain patients: divide the corpus callosum down the middle, and you effectively have two separate brains that don’t communicate. Tell the half without the speech centre to perform some random task, then ask the other one why they did that - and they will flat-out make up some plausible sounding reason.

And the thing is, they haven’t the slightest idea that it isn’t true. To them, it feels exactly like freely choosing to do it, for those made up reasons.

Bits of our brains make us do stuff for their own reasons, and we just make shit up to explain it after the fact. We invent the memory of choosing, about a quarter of a second after we’ve primed our muscles to carry out the choice.

I think a chunk of this comes down to our need to model the thoughts of others (incredibly useful for social animals) - we make everyone out to be these monolithic executive units so that we can predict their actions, and we make ourselves out to be the same so we can slot ourselves into that same reasoning.

Also it would be a bit fucking terrifying to just constantly get surprised by your own actions, blown around like a leaf on the wind without a clue what’s going on, so I think another chunk of it is just larping this “I” person who has a coherent narrative behind it all, to protect your own sanity.

We invent the memory of choosing, about a quarter of a second after we’ve primed our muscles to carry out the choice.

Where can I read more about this?

There was a relevant post on Lemmy the other day:

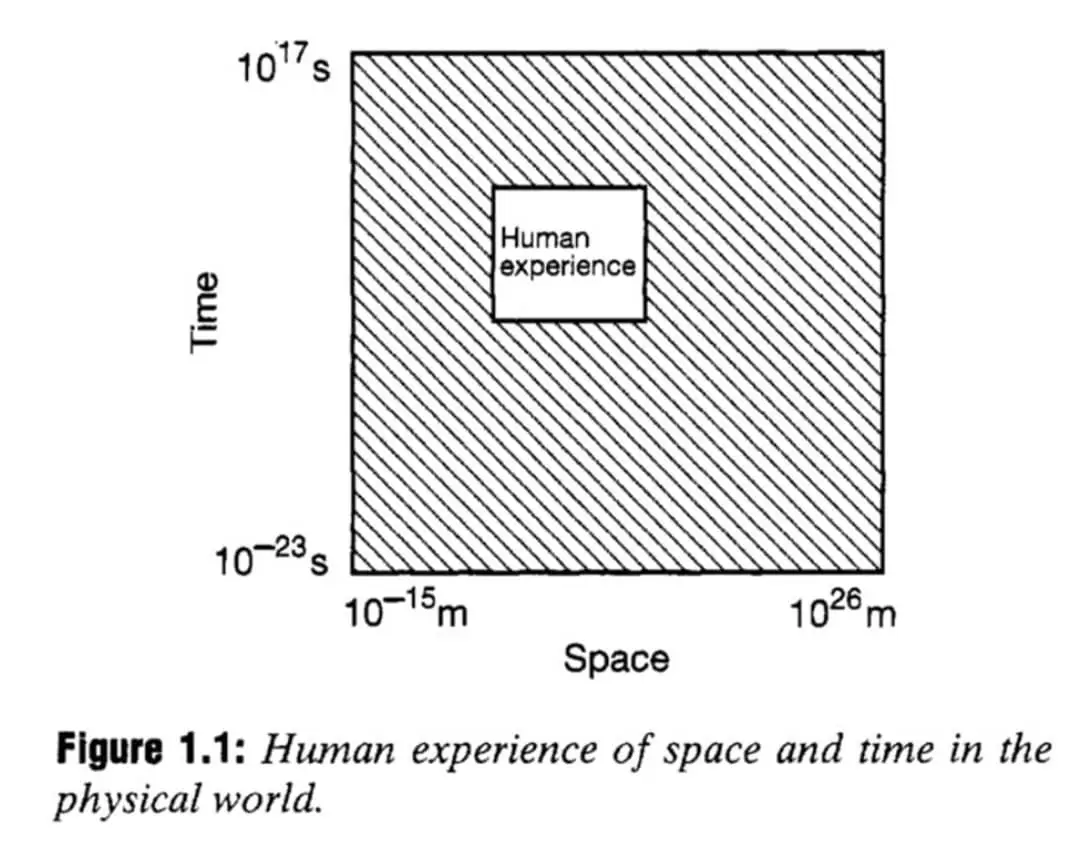

The origin and nature of existence is an epistemological black hole that some people like to plug with “a

wizardgod did it”.The sensation of free will is an emergent property of a lack of awareness of the big stuff, the small stuff, the long stuff, and the short stuff.

I like to look at the illusion of free will as if you’re falling down a pit. You can try to flap your arms or swim, and maybe move yourself a little bit, but at the end, you’re still falling down.

Warning, I came up with this while very high one time, lol, but it’s kind of stuck with me:

Consciousness is a 4-dimensional construct living in a 3-dimensional world. What we experience as the passage of time is just our consciousness traveling/falling along the surface of the 4-dimensional plane/shape that defines our existence.

Feel free to poke all the holes you want in that. lol

There is an old Taoist story about two people floating down a river. One has already decided where he wants the river to take him and is constantly swimming against the current to try to get there, the other just floats along taking in the sights.

They both end up wherever the river takes them, and they both went through the same obstacles and rapids, but when asked how the trip was, one of them is complaining about the whole trip being frustrating and exhausting, while the other had a pleasant time and tells you all about the amazing things they saw on the way.

I love that!

Really illustrates the saying, “go with the flow,” too.

This is basically a spacetime worldline, which is one of those terms that sounds like scifi technobabble even though it’s an actual concept

Couldn’t it also be argued that our lack of awareness of the big stuff also leaves open the possibility of free will?

On a sufficiently large billiards table, it does become hard to prove that some balls don’t spontaneously sink themselves.

That is a clever point but I think it also overly simplifies the nature of reality to such a point that it’s not likely to change any minds.

Here’s my take: the answer is emergent phenomena. We live in a very complex system and in complex systems there are interactions that can only be predicted using systems of equal or higher complexity. So even in case everything is predetermined, it would still be unpredictable and therefore your decisions are basically still up to you and the complex interactions in your brain.

I think this is probably it. I think this argument is strongly related to the idea of consciousness as an emergent property of sensory experience. I find it simple to imagine the idea of a body with no will or no consciousness (i.e., a philosophical zombie). But I find it very difficult, almost impossible, in fact, to imagine a consciousness with no will, even if it’s only the will to think a given thought.

Do we have free will to think a given thought? All of my thoughts just suddenly appear in my mind or are connected to previous thoughts that suddenly appeared in my mind.

I mean, if I said to you, ‘Calculate 13x16’ (or some other sum you don’t know off the top of your head) you could either do it or not do it. That would be a willed choice, whether or not you knew the answer.

My thoughts would be presented based the fact that you’ve asked me to calculate something. At that point, past experiences would guide my path forward. If I felt like doing math, I may do it, if I had poor childhood experiences in math class, I probably wouldn’t. At the end of the day, it’s all based on history or current questions/feelings. In every scenario my thoughts are presented to me. To prove it, ask yourself what your next thought will be. If you’re honest with yourself, you’ll see you can’t answer that question and when you try and force a thought direction, that direction itself is based on your knowledge from the past and that thought was also presented to you.

It’s wild because it absolutely feels like we have free will, but it sure doesn’t look like it. 🤷♂️

This is the problem of original intentionality. There are studies on it, for instance they found that with an mri they can detect when you have come to a decision before your conscious mind realizes you have. Some processes in our brain are outside of our control, because the brain is not just the neocortex but also includes tens of other structures that evolved separately with specific hard-coded purposes, but that doesn’t mean they are not working as a team. I think in any case you are still reaponsible for the decisions you take.

exactly. that for me is in fact the definition of free will

actually this is the definition that first came up on a search

“the power of acting without the constraint of necessity or fate; the ability to act at one’s own discretion”

so yeah we do have free will. the rest is philosophical masturbation

You can also find the definition of magic or telekinesis, but that doesn’t mean we have them, and not all philosophical question are just “masturbation”. It is an interesting question. It is worth taking free will at least axiomatically as our perception of that freedom even if it is truly deterministic.

If you throw a pair of dice, do they still have to roll if their final positions are predetermined from the point that you let go?

One view is that even a deterministic mind still must execute. An illusion of the capacity to choose between multiple options might be necessary to considering those options which leads to the unavoidable conclusion.

Dice do not choose where they roll.

They also do not pretend choosing, or tell themselves any bullshit…

A better question is, is there any difference between the illusion of free will and actual free will. Is there some experiment you could conduct to tell the difference?

Depends, who’s choosing the experiment?

If it’s the illusion of free will then whoever constructed it most likely made sure we wouldn’t have access to those kinds of experiments, or we wouldn’t think of or choose to do them.

Why assume that an illusion must have a constructor?

Our brains cannot store all the experiences we ever make. It rather only stores ‘hunches’ (via many weightings of neurons). In particular, it also mixes multiple experiences together to reinforce such hunches.

This means that despite there being causal reasons why you might e.g. feel uneasy around big dogs, your brain will likely only reproduce a hunch, a gut feeling of fear.

And then because you don’t remember the concrete causal reasons, it feels like a decision to follow your hunch to get the hell out of there.

This feeling of making a decision is made even stronger, because there isn’t just the big-dog-bad-hunch, but also the don’t-show-fear-to-big-dog-hunch and the I’m-in-a-social-situation-and-it-would-be-rude-to-leave-hunch and many others.There is just an insane amount of past experiences and present sensory input, which makes it impossible to trace back why you would decide a certain way. This gives the illusion of there being no reasons, of free will.

Maybe look up “compatibilism”. It’s a philosophy proposing that both exist.

TIL!

I just made up my own term for it in another post :)

You’re conscious of the decisions you make. Sure they’re the result of a million different variables, chemicles, memories, and predetermined traits, but some of that is active. You are making the choice. Whether you could have made a different one or not doesn’t affect what the choice feels like

Honorary mention, Kurtzgesagt/In a Nutshell https://youtu.be/UebSfjmQNvs?feature=shared

Roger Penrose is pretty much the only dude looking into consciousness from the perspective of a physicist

He thinks consciousness has to do with “quantum bubble collapse” happening inside our brains at a very very tiny level.

That’s the only way free will could exist.

If consciousness is anything else, then everything is predetermined.

Like, imagine dropping a million bouncy balls off the hoover dam. You’ll never get the same results twice.

However, that’s because you’ll never get the same conditions twice.

If the conditions are exactly the same down to an atomic level… You’ll get the same results every time

What would give humans free will would be the inherent randomness if the whole “quantum bubble collapse” was a fundamental part of consciousness.

That still wouldn’t guarantee free will, but it would make it possible.

There’s also the whole thing where what we think of as our consciousness isn’t actually running the show. It’s just a narrator that’s summarizing everything up immediately after it happened. What’s actually calling the shot is other parts of our brains, neurons in our gut, and what controls our hormones.

We don’t know if that’s not true either. But if it was, each person as a thing would have free will, it’s just what we think of as that person does not have free will.

Sounds batshit crazy and impossible, until you read up on the studies on people who had their brains split in half at different stages of mental development.

There’s a scary amount of shit we don’t know about “us”. And an even scarier amount we don’t know about how much variation there is with all that

Roger Penrose is pretty much the only dude looking into consciousness from the perspective of a physicist

I would recommend reading the philosophers Jocelyn Benoist and Francois-Igor Pris who argue very convincingly that both the “hard problem of consciousness” and the “measurement problem” stem from the same logical fallacies of conflating subjectivity (or sometimes called phenomenality) with contextuality, and that both disappear when you make this distinction, and so neither are actually problems for physics to solve but are caused by fallacious reasoning in some of our a priori assumptions about the properties of reality.

Benoist’s book Toward a Contextual Realism and Pris’ book Contextual Realism and Quantum Mechanics both cover this really well. They are based in late Wittgensteinian philosophy, so maybe reading Saul Kripke’s Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language is a good primer.

That’s the only way free will could exist…What would give humans free will would be the inherent randomness if the whole “quantum bubble collapse” was a fundamental part of consciousness.

Even if they discover quantum phenomena in the brain, all that would show is our brain is like a quantum computer. But nobody would argue quantum computers have free will, do they? People often like to conflate the determinism/free will debate with the debate over Laplacian determinism specifically, which should not be conflated, as randomness clearly has nothing to do with the question of free will.

If the state forced everyone into a job for life the moment they turned 18, but they chose that job using a quantum random number generator, would it be “free”? Obviously not. But we can also look at it in the reverse sense. If there was a God that knew every decision you were going to make, would that negate free will? Not necessarily. Just because something knows your decision ahead of time doesn’t necessarily mean you did not make that decision yourself.

The determinism/free will debate is ultimately about whether or not human decisions are reducible to the laws of physics or not. Even if there is quantum phenomena in the brain that plays a real role in decision making, our decisions would still be reducible to the laws of physics and thus determined by them. Quantum mechanics is still deterministic in the nomological sense of the word, meaning, determinism according to the laws of physics. It is just not deterministic in the absolute Laplacian sense of the word that says you can predict the future with certainty if you knew all properties of all systems in the present.

If the conditions are exactly the same down to an atomic level… You’ll get the same results every time

I think a distinction should be made between Laplacian determinism and fatalism (not sure if there’s a better word for the latter category). The difference here is that both claim there is only one future, but only the former claims the future is perfectly predictable from the states of things at present. So fatalism is less strict: even in quantum mechanics that is random, there is a single outcome that is “fated to be,” but you could never predict it ahead of time.

Unless you ascribe to the Many Worlds Interpretation, I think you kind of have to accept a fatalistic position in regards to quantum mechanics, mainly due not to quantum mechanics itself but special relativity. In special relativity, different observers see time passing at different rates. You can thus build a time machine that can take you into the future just by traveling really fast, near the speed of light, then turning around and coming back home.

The only way for this to even be possible for there to be different reference frames that see time pass differently is if the future already, in some sense, pre-exists. This is sometimes known as the “block universe” which suggests that the future, present, and past are all equally “real” in some sense. For the future to be real, then, there has to be an outcome of each of the quantum random events already “decided” so to speak. Quantum mechanics is nomologically deterministic in the sense that it does describe nature as reducible to the laws of physics, but not deterministic in the Laplacian sense that you can predict the future with certainty knowing even in principle. It is more comparable to fatalism, that there is a single outcome fated to be (that is, again, unless you ascribe to MWI), but it’s impossible to know ahead of time.

Even if they discover quantum phenomena in the brain

There 100% are…

Penrose thinks they’re responsible for consciousness.

Because we also don’t know what makes anesthesia stop consciousness. And anesthesia stops consciousness and stops the quantum process.

Now, the math isn’t clean. I forget which way it leans, but I think it’s that consciousness kicks out a little before the quantum action is fully inhibited?

It’s been a minute, and this shit isn’t simple.

Unless you ascribe to the Many Worlds Interpretation

This is incompatible with that.

It’s the quantum wave function collapse that’s important. There’s no spinning out where multiple things happen, there is only one thing. After wave collapse, is when you look in the box and see if the cats dead.

In a sense it’s the literal “observer effect” happening our head.

And that is probably what consciousness is.

It’ll just take a while till we can prove it. And Penrose will probably be dead by then. But so was Einstein before Penrose proved most of his shit was true

That’s how science works. Most won’t know who Penrose is till he’s dead.

I don’t think it’s incompatible with many worlds, unless I’m misunderstanding something. The many worlds interpretation means that the observer doesn’t collapse the wave function, but rather becomes entangled with it. It only apparently collapses because we only perceive a “slice” of the wave function. (For whatever reason).

I think this is still compatible with Penrose’s ideas, just not in the way he presents it. Anyway, I think he’s not really explaining consciousness, but rather a piece of how it could be facilitated in the brain.

There are quantum phenomenon in a piece of bread. That doesn’t mean bread is conscious.

Penrose has never proved that the quantum effects affect neurons macroscopically.

Quantum computers run at near absolute zero temperature and isolated from all vibrations in order to maintain superposition. The brain is a horrible environment for a quantum computer.

Anesthesia is a chemical signal blocker. If consciousness was quantum, it couldn’t affect it.

Penrose’s work is “God in the gaps” or in his case “quantum in the gaps” explanation of consciousness. His claims were made before we had functional quantum computers and precise categorization of neurotransmitters that anesthesia chemicals bind to to block your natural neurotransmitters.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-does-anesthesia-work/

There 100% are…

If you choose to believe so, like I said I don’t really care. Is a quantum computer conscious? I think it’s a bit irrelevant whether or not they exist. I will concede they do for the sake of discussion.

Penrose thinks they’re responsible for consciousness.

Yeah, and as I said, Penrose was wrong, not because the measurement problem isn’t the cause for consciousness, but that there is no measurement problem nor a “hard problem.” Penrose plays on the same logical fallacies I pointed out to come to believe there are two problems where none actually exist and then, because both problems originate from the same logical fallacies. He then notices they are similar and thinks “solving” one is necessary for “solving” the other, when neither problems actually existed in the first place.

Because we also don’t know what makes anesthesia stop consciousness. And anesthesia stops consciousness and stops the quantum process.

You’d need to define what you mean more specifically about “consciousness” and “quantum process.” We don’t remember things that occur when we’re under anesthesia, so are we saying memory is consciousness?

Now, the math isn’t clean. I forget which way it leans, but I think it’s that consciousness kicks out a little before the quantum action is fully inhibited? It’s been a minute, and this shit isn’t simple.

Sure, it’s not simple, because the notion of “consciousness” as used in philosophy is a very vague and slippery word with hundreds of different meanings depending on the context, and this makes it seem “mysterious” as its meaning is slippery and can change from context to context, making it difficult to pin down what is even being talked about.

Yet, if you pin it down, if you are actually specific about what you mean, then you don’t run into any confusion. The “hard problem of consciousness” is not even a “problem” as a “problem” implies you want to solve it, and most philosophers who advocate for it like David Chalmers, well, advocate for it. They spend their whole career arguing in favor of its existence and then using it as a basis for their own dualistic philosophy. It is thus a hard axiom of consciousness and not a hard problem. I simply disagree with the axioms.

Penrose is an odd case because he accepts the axioms and then carries that same thinking into QM where the same contradiction re-emerges but actually thinks it is somehow solvable. What is a “measurement” if not an “observation,” and what is an “observation” if not an “experience”? The same “measurement problem” is just a reflection of the very same “hard problem” about the supposed “phenomenality” of experience and the explanatory gap between what we actually experience and what supposedly exists beyond it.

It’s the quantum wave function collapse that’s important.

Why should I believe there is a physical collapse? This requires you to, again, posit that there physically exists something that lies beyond all possibilities of us ever observing it (paralleling Kant’s “noumenon”) which suddenly transforms itself into something we can actually observe the moment we try to look at it (paralleling Kant’s “phenomenon”). This clearly introduces an explanatory gap as to how this process occurs, which is the basis of the measurement problem in the first place.

There is no reason to posit a physical “collapse” or even that there exists at all a realm of waves floating about in Hilbert space. These are unnecessary metaphysical assumptions that are purely philosophical and contribute nothing but confusion to an understanding of the mathematics of the theory. Again, just like Chalmers’ so-called “hard problem,” Penrose is inventing a problem to solve which we have no reason to believe is even a problem in the first place: nothing about quantum theory demands that you believe particles really turn into invisible waves in Hilbert space when you aren’t looking at them and suddenly turn back into visible particles in spacetime when you do look at them.

That’s entirely metaphysical and arbitrary to believe in.

There’s no spinning out where multiple things happen, there is only one thing. After wave collapse, is when you look in the box and see if the cats dead. In a sense it’s the literal “observer effect” happening our head. And that is probably what consciousness is.

There is only an “observer effect” if you believe the cat literally did turn into a wave and you perturbed that wave by looking at it and caused it to “collapse” like a house of cards. What did the cat see in its perspective? How did it feel for the cat to turn into a wave? The whole point of Schrodinger’s cat thought experiment was that Schrodinger was trying to argue against believing particles really turn into waves because then you’d have to believe unreasonable things like cats turning into waves.

All of this is entirely metaphysical, there is no observations that can confirm this interpretation. You can only justify the claim that cats literally turn into waves when you don’t look at them and there is a physical collapse of that wave when you do look at them on purely philosophical grounds. It is not demanded by the theory at all. You choose to believe it purely on philosophical grounds which then leads you to think there is some “problem” with the theory that needs to be “solved,” but it is purely metaphysical.

There is no actual contradiction between theory and evidence/observation, only contradiction between people’s metaphysical assumptions that they refuse to question for some reason and what they a priori think the theory should be, rather than just rethinking their assumptions.

That’s how science works. Most won’t know who Penrose is till he’s dead.

I’d hardly consider what Penrose is doing to be “science” at all. All these physical “theories of consciousness” that purport not to just be explaining intelligence or self-awareness or things like that, but more specifically claim to be solving Chalmers’ hard axiom of consciousness (that humans possess some immaterial invisible substance that is somehow attached to the brain but is not the brain itself), are all pseudoscience, because they are beginning with an unreasonable axiom which we have no scientific reason at all to take seriously and then trying to use science to “solve” it.

It is no different then claiming to use science to try and answer the question as to why humans have souls. Any “scientific” approach you use to try and answer that question is inherently pseudoscience because the axiomatic premise itself is flawed: it would be trying to solve a problem it never established is even a problem to be solved in the first place.

I agree with some of what you’re saying, but can you explain (in simple terms please) how the hard problem doesn’t exist? I’m not quite following. The subjective experience of consciousness is directly observable, and definitely real, no?

(I don’t think adding some metaphysical element does much of anything, and Penrose still doesn’t really explain it, just provides a potential mechanism for it in the brain. It’s still a real “thing”, unexplained by current physics though.)

Also, to your other point, my I believe everything is just an evolving wave function. All waves all the time, and we only perceive a slice of it. (Which has something to do with consciousness, but nobody really knows exactly how). The Copenhagen interpretation is just how the many worlds universe appears to behave to a conscious observer.

The subjective experience of consciousness is directly observable, and definitely real, no?

Experience is definitely real, but there is no such thing as “subjective experience.” It is not logically possible to say there is “subjective experience” without inherently entailing that there is some sort of “objective experience,” in the same way that saying something is “inside of” something makes no sense unless there is an “outside of” it. Without implicitly entailing some sort of “objective experience” then the qualifier “subjective” would become meaningless.

If you associate “experience” with “minds,” then you’d be implying there is some sort of objective mind, i.e. a cosmic consciousness of some sorts. Which, you can believe that, but at that point you’ve just embraced objective idealism. The very usage of the term “subjective experience” that is supposedly inherently irreducible to non-minds inherently entails objective idealism, there is no way out of it once you’ve accepted that premise.

The conflation between experience with “subjectivity” is largely done because we all experience the world in a way unique to us, so we conclude experience is “subjective.” But a lot of things can be experienced differently between different observers. Two observers, for example, can measure the same object to be different velocities, not because velocity is subjective, but because they occupy different frames of reference. In other words, the notion that something being unique to us proves it is “subjective” is a non sequitur, there can be other reasons for it to be unique to us, which is just that nature is context-dependent.

Reality itself depends upon where you are standing in it, how you are looking at it, everything in your surroundings, etc, how everything relates to everything else from a particular reference frame. So, naturally, two observers occupying different contexts will perceive the world differently, not because their perception is “subjective,” but in spite of it. We experience the world as it exists independent of our observation of it, but not independent of the context of our observation. Experience itself is not subjective, although what we take experience to be might be subjective.

We can misinterpret things for example, we can come to falsely believe we experienced some particular thing and later it turns out we actually perceived something else, and thus were mistaken in our initial interpretation which we later replaced with a new interpretation. However, at no point did it become false that there was experience. Reality can never be true or false, it always just is what it is. The notion that there is some sort of “explanatory gap” between what humans experience and some sort of cosmic experience is just an invented problem. There is no gap because what we experience is indeed reality independent of conscious observers being there to interpret it, but absolutely dependent upon the context under which it is observed.

Again, I’d recommend reading Jocelyn Benoist’s Toward a Contextual Realism. All this is explained in detail and any possible rebuttal you’re thinking of has already been addressed. People are often afraid of treating experience as real because they operate on this Kantian “phenomenal-noumenal” paradigm (inherently implied by the usage of “subjective experience”) and then think if they admit that this unobservable “noumenon” is a meaningless construct then they have to default to only accepting the “phenomenon,” i.e. that there’s only “subjective experience” and we’re all “trapped in our minds” so to speak. But the whole point of contextual realism is to point out this fear is unfounded because both the phenomenal and noumenal categories are problematic and both have to be discarded: experience is not “phenomenal” as a “phenomenal” means “appearance of reality” but it is not the appearance of reality but is reality.

You only enter into subjectivity, again, when you take reality to be something, when you begin assigning labels to it, when you begin to invent abstract categories and names to try and categorize what you are experiencing. (Although the overwhelming majority of abstract categories you use were not created by you but are social constructs, part of what Wittgenstein called the “language game.”)

(I don’t think adding some metaphysical element does much of anything, and Penrose still doesn’t really explain it, just provides a potential mechanism for it in the brain. It’s still a real “thing”, unexplained by current physics though.)

We don’t need more metaphysical elements, we need less. We need to stop presuming things that have no reason to be presumed, then presuming other things to fix contradictions created by those false presumptions. We need to discard those bad assumptions that led to the contradiction in the first place (discard then phenomenal-noumenal distinction entirely, not just one or the other).

Also, to your other point, my I believe everything is just an evolving wave function.

This is basically the Many Worlds Interpretation. I don’t really buy it because we can’t observe wave functions, so if the entire universe is made of wave functions… how does that explain what we observe? You end up with an explanatory gap between what we observe and the mathematical description.

The whole point of science is to explain the reality which we observe, which is synonymous with experience, which again experience just is reality. That’s what science is supposed to do: explain experiential reality, so we have to tie it back to experience, what Bell called “local beables,” things we can actually point to identify in our observations.

The biggest issue with MWI is that there is simply no way to tie it back to what we actually observe because it contains nothing observable. There is an explanatory gap between the world of waves in Hilbert space and what we actually observe in reality.

The Copenhagen interpretation is just how the many worlds universe appears to behave to a conscious observer.

What you’ve basically done is just wrapped up the difficult question of how the invisible world of waves in Hilbert space converts itself to the visible world of particles in spacetime by just saying “oh it has something to do with our consciousness.” I mean, sure, if you find that to be satisfactory, I personally don’t.

If you choose to believe so, like I said I don’t really care

What?

We literally and scientifically know that it does…

I just want to thank you for typing that ahead of all that other shit you pulled out of your ass.

No one’s reading it anyways, but at least they won’t feel bad for skipping it

No, we don’t know the brain is making use of any quantum phenomena. At best if there is any quantum phenomena in the brain it would just contribute noise. The idea that interference phenomena is actually made use of in the brain for computation is just not backed by anything.

Inception helped to bring the Penrose Stairs back into popularity and Penrose tiles are still a popular example of aperiodic tiling, so I suspect enough of the public has a connection to who he is.

Even if the brain is a quantum computer, it’s quantum dice rolls controlling your neurons. So quantum consciousness doesn’t enable the possibility free will.

Just going to throw out a really good read: Determined by Robert Sapolky. (Behave is also really good.)

He doesn’t really convince me of the core thesis that free will doesn’t exist, or that some of his proposed changes to the legal system to “recognize the absence of free will” in the second half are good courses of action, but he does do a great job of demonstrating what makes us tick from a variety of lenses, how much environmental factors play a role in behavior, and generally arguing to approach people with more empathy and recognition that we might be more like them in a similar situation than we think.

(It is heavy. It’s long and goes into some depth on different fields. But he lays out the main ideas you need to know and doesn’t assume that much knowledge, just a will to learn.)

Behave is incredible.

I read a fucking lot of books about what makes us tick. Behave is (tied for) my favorite. He does actually hint down the determinism path a little in behave, but he goes all in on Determined.

I would still probably generally recommend Behave over Determined, but Determined is directly relevant to the OP.

I have heard somewhere that some people seemed to believe that behind each human’s actions, there is some kind of “daemon” that is invisible, but moving the humans like puppets.

This is conceptualized in the theater mask, through which one can speak.

The daemon speaks through the human as a theater actor would speak through a mask. (The latin word for that mask is “persona” (literally “sound-through”) and that’s why we call a person a person today (because they are controlled by a daemon who speaks through them)).

My deamon is now telling you this theory is convoluted and stupid.

The most accurate answer is: We don’t know.

But there are pieces of scientific evidence that suggest our sense of free will is just another perception process that happens in our brains. Specifically I’m thinking about people who have problems in their brain that make them feel like they AREN’T the one controlling what they do. For example people suffering from derealization - https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depersonalization-derealization-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352911

EDIT

As to why our brains have a process that gives us a perception of free will, that’s a much harder question that i think science currently only has conjecture on. If i had to guess I’d guess that either there’s an evolutionary advantage to it, or it’s an emergent property that arises from all the parts of the brain being connected in the way they are

I forget which philosopher said this but he said something along the lines of if you have the desire and the capacity for an action you do, then deterministic or not, you chose that action. If the tide pulls me where I was already swimming, I still chose to swim there, even if some other force took me half of the way.

But where does your desire and capacity to do that thing come from? It arises from the physical arrangement of neurons/hormones/etc. in your brain and body

Why are you separating “you” from the choices your physical self is making?

I’m not. Did you reply to the correct comment?

For the same reason that I feel like I’m still right now, while I’m actually spinning and hurtling through space at incredible speed.

ludicrous speed